Full size

image available below |

Dyslexia and Language

Brain Areas

The

learning disability dyslexia, which centers on

difficulties in reading, once stumped scientists. Since

dyslexics often have good intelligence and even may be

gifted in some areas, it was thought that a little

motivation could get them on the right track. Now

researchers not only know that dyslexia is born of

biology, but they also are getting closer to confirming

the key brain areas that are affected. New insights will

help pinpoint therapies and improve treatment.

Albert Einstein

was a genius. And a dyslexic.

The fact that the

reading disability, dyslexia - often marked by deficits

in the decoding of words - can affect smart people, even

some famously knowledgeable, once perplexed scientists.

Many assumed that laziness was the cause.

Now research confirms

that more than a kick in the butt is needed to jumpstart

dyslexics' stall in reading. Studies show a biological

basis for this disability that affects millions of

American children and adults. One line of research

indicates that dyslexics use the brain regions that

process written language differently than those without

the disorder.

New advances are leading to:

- Earlier diagnosis and treatment of dyslexia.

- Fine-tuning of therapies.

- A better understanding of the nature of dyslexia.

For decades

after researchers first described dyslexia, many people

contended that it stemmed from a "slacker" attitude.

Then, almost a century later, scientists began to

unearth hints that the disorder was backed by biology.

In 1979 a report indicated that anatomical abnormalities

existed in a dyslexic patient. The left side of the

brain of the 20-year-old who died accidentally depicted

disorganization in the cells that control language

areas.

The finding

caused researchers to investigate the brain's

involvement in dyslexia.

Many scientists have

identified brain regions related to dyslexia with

high-tech imaging techniques that photograph the brain

in action. The tools have helped them link the

disability to speech sound processing, vision and

language brain systems. Today researchers are

systematically scrutinizing large numbers of dyslexics

to determine which areas of the brain are the most

involved and to understand how they relate to each other

and contribute to different degrees and varieties of the

disability. Dyslexia's symptoms, which may include

deficits in spelling, in recognizing sounds in words, in

processing rapid visual information and in saying words

quickly when put on the spot, have made it difficult for

researchers to tease apart the key brain regions

involved.

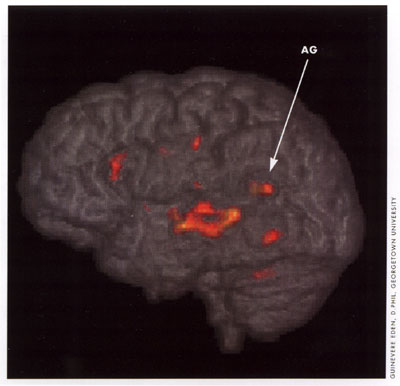

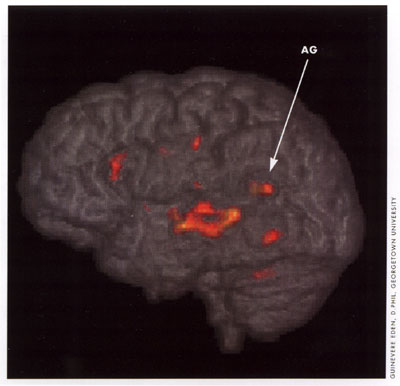

While the

areas most central to the disability are still

uncertain, many researchers suspect that the brain areas

that control language play a critical role. One of these

areas that keeps coming up in studies is the angular

gyrus (AG). Located toward the back of the brain, the AG

translates the mass of words and letters we encounter in

day-to-day life into language.

Some researchers

believe the area, which is known to be involved in

normal reading, is a key component of an overall

"reading pathway" in the brain. Recent studies of a

variety of reading and language tasks in dyslexic

individuals showed less activity in the AG than those

without the disability. The researchers suspect that

this part of the brain does not function normally in

dyslexics.

Some

scientists speculate that dyslexics use the area

inadequately and may compensate by using other brain

areas, such as the inferior frontal gyrus, which is

located in the front of the brain, and is associated

with spoken language. For example, dyslexics who say the

words they are reading under their breath may rely

heavily on this area to get through a passage of text,

according to one theory.

Many researchers also

are using imaging techniques to see if the behavioral

interventions sometimes used to treat those with

dyslexia actually modify brain activity. One group is

reviewing three separate interventions thought to target

either the brain system that processes written language,

the speech sound processing system or the visual system.

The results could

help confirm the brain areas that are common to the many

forms of the disability and lead to a fine-tuning of

interventions.

Several

imaging studies of reading and language skills

show that the AG is involved in dyslexia. One

group of researchers currently is studying how

dyslexics perform pig latin tasks compared to

normal readers. Pig latin requires dissecting and

reordering the sounds within a word. For example,

if a word begins with a consonant, the first

letter is moved to the end of the word and "ay" is

added. "Pig" becomes "igpay." It is a difficult

test for dyslexics because it challenges their

ability to sound out written words as well as

their memory skills. The image above shows that

activity in the AG is increased in a normal reader

who performs the pig latin task. The researchers

suspect that the activity will be lower in

dyslexic readers.

|

|

Image by Guinevere Eden, D.Phil, Georgetown

University |

For more information please contact Leah Ariniello,

Science Writer, Society for Neuroscience, 11 Dupont

Circle, NW, Suite 500, Washington DC 20036. |