Imagine that when you see a city's skyline, you

taste blackberries. Or maybe when you hear a violin, you feel a tickle on

your left knee. Perhaps you are completely convinced that Wednesdays are

light red. If you have experiences like these, you might have synesthesia. Imagine that when you see a city's skyline, you

taste blackberries. Or maybe when you hear a violin, you feel a tickle on

your left knee. Perhaps you are completely convinced that Wednesdays are

light red. If you have experiences like these, you might have synesthesia.

What is synesthesia?Synesthesia is a condition in which one sense

(for example, hearing) is simultaneously perceived as if by one or more

additional senses such as sight. Another form of synesthesia joins objects

such as letters, shapes, numbers or people's names with a sensory

perception such as smell, color or flavor. The word synesthesia comes from

two Greek words, syn (together) and aisthesis (perception).

Therefore, synesthesia literally means "joined perception."

Synesthesia can involve any of the senses. The most common form,

colored letters and numbers, occurs when someone always

sees a certain color in response to a certain letter of the alphabet or

number. For example, a synesthete (a person with synesthesia) might see

the word "plane" as mint green or the number

"4" as dark brown. There are also synesthetes

who hear sounds in response to smell, who smell in response to touch, or

who feel something in response to sight. Just about any combination of the

senses is possible. There are some people who possess synesthesia

involving three or even more senses, but this is extremely rare.

Synesthesia can involve any of the senses. The most common form,

colored letters and numbers, occurs when someone always

sees a certain color in response to a certain letter of the alphabet or

number. For example, a synesthete (a person with synesthesia) might see

the word "plane" as mint green or the number

"4" as dark brown. There are also synesthetes

who hear sounds in response to smell, who smell in response to touch, or

who feel something in response to sight. Just about any combination of the

senses is possible. There are some people who possess synesthesia

involving three or even more senses, but this is extremely rare.

Synesthetic perceptions are specific to each person. Different people

with synesthesia almost always disagree on their perceptions. In other

words, if one synesthete thinks that the letter "q" is colored blue, another synesthete might see

"q" as orange.

Although there is no officially

established method of diagnosing synesthesia, some guidelines have been

developed by Richard Cytowic, MD, a leading synesthesia researcher. Not

everyone agrees on these standards, but they provide a starting point for

diagnosis. According to Cytowic, synesthetic perceptions are:

-

Involuntary: synesthetes do not actively think about

their perceptions; they just happen.

Involuntary: synesthetes do not actively think about

their perceptions; they just happen.

-

Projected: rather than experiencing something in the

"mind's eye," as might happen when you are asked to imagine a color, a

synesthete often actually sees a color projected outside of the body.

Projected: rather than experiencing something in the

"mind's eye," as might happen when you are asked to imagine a color, a

synesthete often actually sees a color projected outside of the body.

-

Durable and

generic: the perception must be the same every time; for

example, if you taste chocolate when you hear Beethoven's Violin

Concerto, you must always taste chocolate when you hear it; also, the

perception must be generic -- that is, you may see colors or lines or

shapes in response to a certain smell, but you would not see something

complex such as a room with people and furniture and pictures on the

wall. Durable and

generic: the perception must be the same every time; for

example, if you taste chocolate when you hear Beethoven's Violin

Concerto, you must always taste chocolate when you hear it; also, the

perception must be generic -- that is, you may see colors or lines or

shapes in response to a certain smell, but you would not see something

complex such as a room with people and furniture and pictures on the

wall.

-

Memorable: often, the secondary synesthetic perception

is remembered better than the primary perception; for example, a

synesthete who always associates the color purple with the name "Laura" will often remember that a woman's name is

purple rather than actually remembering "Laura."

Memorable: often, the secondary synesthetic perception

is remembered better than the primary perception; for example, a

synesthete who always associates the color purple with the name "Laura" will often remember that a woman's name is

purple rather than actually remembering "Laura."

-

Emotional: the perceptions may cause emotional

reactions such as pleasurable feelings.

Emotional: the perceptions may cause emotional

reactions such as pleasurable feelings.

Who has it? Estimates

for the number of people with synesthesia range from 1 in 200 to 1 in

100,000. There are probably many people who have the condition but do not

realize what it is. Estimates

for the number of people with synesthesia range from 1 in 200 to 1 in

100,000. There are probably many people who have the condition but do not

realize what it is.

Synesthetes tend to be:

-

Women: in

the U.S., studies show that three times as many women as men have

synesthesia; in the U.K., eight times as many women have been reported

to have it. The reason for this difference is not known. Women: in

the U.S., studies show that three times as many women as men have

synesthesia; in the U.K., eight times as many women have been reported

to have it. The reason for this difference is not known.

-

Left-handed: synesthetes are more likely to be

left-handed than the general population.

Left-handed: synesthetes are more likely to be

left-handed than the general population.

-

Neurologically

normal: synesthetes are of normal (or possibly above average)

intelligence, and standard neurological exams are normal. Neurologically

normal: synesthetes are of normal (or possibly above average)

intelligence, and standard neurological exams are normal.

-

In the same

family: synesthesia appears to be inherited in some fashion; it

seems to be a dominant trait and it may be on the X-chromosome. In the same

family: synesthesia appears to be inherited in some fashion; it

seems to be a dominant trait and it may be on the X-chromosome.

Some celebrated people who may have

had synesthesia include:

-

Vasily Kandinsky (painter,

1866-1944) Vasily Kandinsky (painter,

1866-1944)

-

Olivier Messiaen (composer,

1908-1992) Olivier Messiaen (composer,

1908-1992)

-

Charles Baudelaire (poet,

1821-1867) Charles Baudelaire (poet,

1821-1867)

-

Franz Liszt (composer,

1811-1886) Franz Liszt (composer,

1811-1886)

-

Arthur Rimbaud (poet,

1854-1891) Arthur Rimbaud (poet,

1854-1891)

-

Richard Phillips Feynman

(physicist, 1918-1988) Richard Phillips Feynman

(physicist, 1918-1988)

It is possible that some of these people merely expressed synesthetic

ideas in their arts, although some of them undoubtedly did have

synesthesia.

The Biological Basis of SynesthesiaSome

scientists believe that synesthesia results from "crossed-wiring" in the

brain. They hypothesize that in synesthetes, neurons and synapses that are

"supposed" to be contained within one sensory system cross to another

sensory system. It is unclear why this might happen but some researchers

believe that these crossed connections are present in everyone at birth,

and only later are the connections refined. In some studies, infants

respond to sensory stimuli in a way that researchers think may involve

synesthetic perceptions. It is hypothesized by these researchers that many

children have crossed connections and later lose them. Adult synesthetes

may have simply retained these crossed connections.

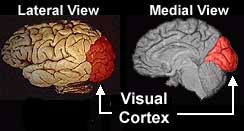

It is unclear which parts of the brain are involved

in synesthesia. Richard Cytowic's research has led him to believe that the

limbic

system is primarily responsible for synesthetic experiences. The

limbic system includes several brain structures primarily

responsible for regulating our emotional responses. Other research,

however, has shown significant activity in the cerebral

cortex during synesthetic experiences. In fact, studies have

shown a particularly interesting effect in the cortex: colored-hearing

synesthetes have been shown to display activity in several areas of the

visual cortex when they hear certain words. In particular, areas of

the visual cortex associated with processing color are activated when the

synesthetes hear words. Non-synesthetes do not show activity in these

areas, even when asked to imagine colors or to associate certain colors

with certain words. It is unclear which parts of the brain are involved

in synesthesia. Richard Cytowic's research has led him to believe that the

limbic

system is primarily responsible for synesthetic experiences. The

limbic system includes several brain structures primarily

responsible for regulating our emotional responses. Other research,

however, has shown significant activity in the cerebral

cortex during synesthetic experiences. In fact, studies have

shown a particularly interesting effect in the cortex: colored-hearing

synesthetes have been shown to display activity in several areas of the

visual cortex when they hear certain words. In particular, areas of

the visual cortex associated with processing color are activated when the

synesthetes hear words. Non-synesthetes do not show activity in these

areas, even when asked to imagine colors or to associate certain colors

with certain words.

Synesthesia and the Study of ConsciousnessMany researchers are

interested in synesthesia because it may reveal something about human

consciousness. One of the biggest mysteries in the study of consciousness

is what is called the "binding problem." No one knows how we bind all of

our perceptions together into one complete whole. For example, when you

hold a flower, you see the colors, you see its shape, you smell its scent,

and you feel its texture. Your brain manages to bind all of these

perceptions together into one concept of a flower. Synesthetes might have

additional perceptions that add to their concept of a flower. Studying

these perceptions may someday help us understand how we perceive our

world. |

Hear IT!

Hear IT!

References and more

information on synesthesia, see:

References and more

information on synesthesia, see:

![[email]](Synesthesia_files/menue.gif)